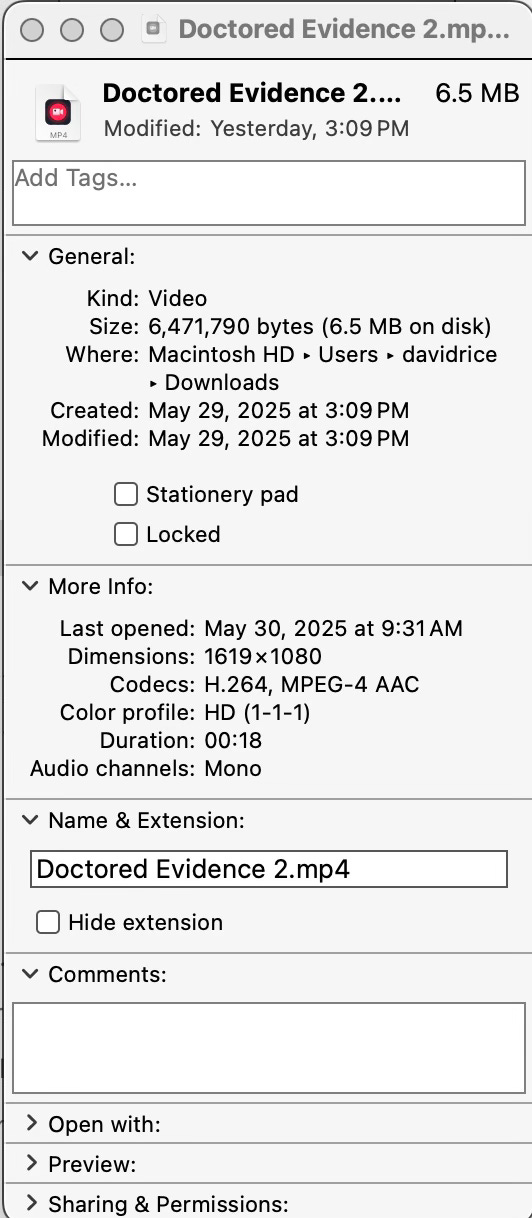

The doctored video that was originally uploaded on May 29th at 12 pm. Notice the editing jump after John Garrity speaks.

This screen recording was created at 3:09 pm. The file was uploaded originally around 12:00 pm on May 29, 2025.

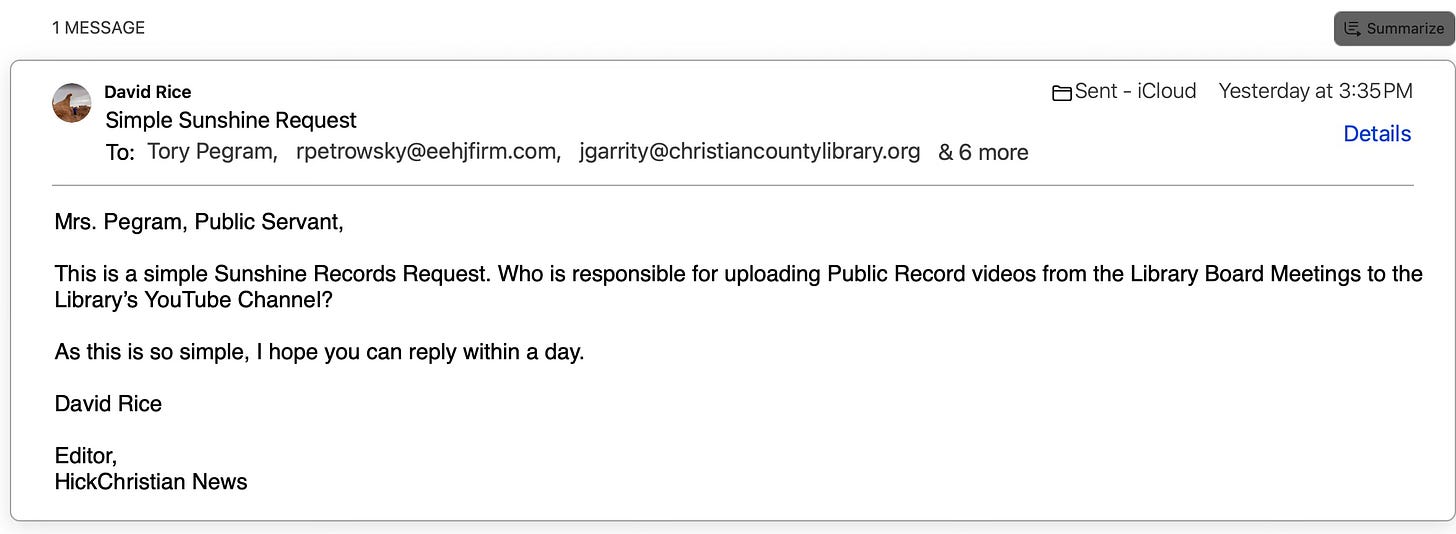

The original link is now broken and you cannot go to it after I sent this email at 3:35 pm.

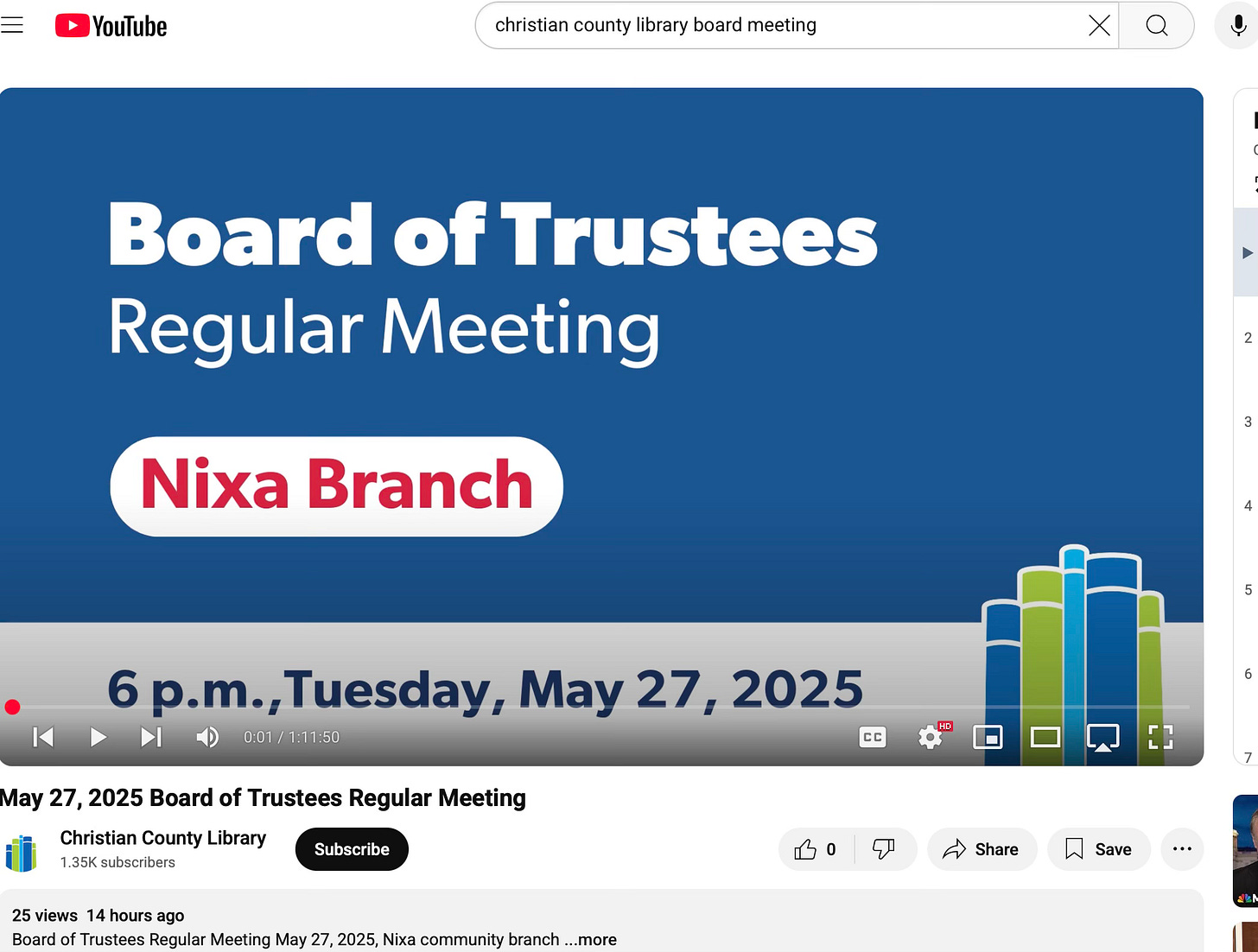

The new link is here.

This new video is 16 seconds longer than the original, meaning that the one edit I caught isn’t the only edit. This video is 1:11:50 long. The previous video is 1:11:34. Perhaps, they have edited other videos in the past?

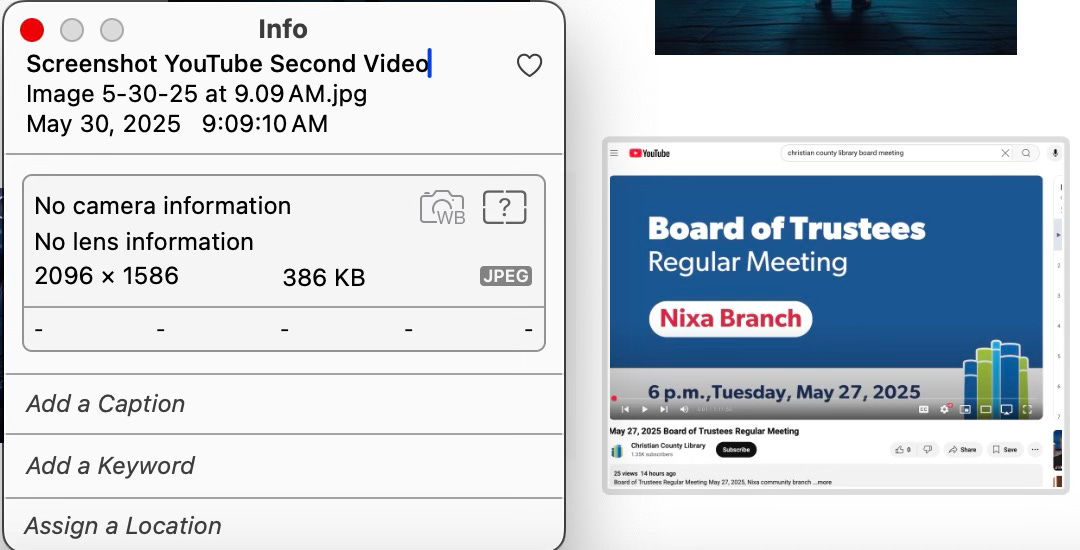

I did this screen grab at 9:09 am. 14 hours before 9 am on May 30th would have been 7 pm on May 29th.

The new video was uploaded at 7 pm, past closing time for the branch to be open. They did this after hours. They have not responded to my email on who is responsible for uploading Public Records to their YouTube channel.

"Caught Red-Handed: The After-Hours Cover-Up"

The library's response to inquiry reveals the deliberate nature of their sunshine law violations. After I documented the edited video at 3:09 PM and sent a sunshine request at 3:35 PM asking who was responsible for uploading public records, the library immediately removed the doctored video.

By 7:00 PM—immediately after the Nixa branch's closing hours—a new version appeared with the previously edited content restored. The replacement video runs 1:11:50, a full 16 seconds longer than the original 1:11:34 recording, indicating multiple edits were made to the public record beyond the violation documented by this investigation.

The after-hours timing suggests library staff recognized the legal jeopardy their editing created and worked outside normal business hours to correct the violation. The library has not responded to the sunshine request identifying who handles YouTube uploads or acknowledged the editing of public records.

This timeline proves they knew exactly what they were doing wrong and moved quickly to cover their tracks once caught. The 16-second difference suggests this is a pattern, not an isolated incident.

The library's response timeline reveals consciousness of guilt. Within 3.5 hours of receiving a sunshine law inquiry about video editing, library staff worked after normal business hours to remove the doctored recording and replace it with a complete version. The corrected video, uploaded at approximately 7:00 PM, runs 16 seconds longer than the original—proving the documented editing violation was only part of the content illegally removed from the public record.

What’s in the missing video that I first noticed, not mentioning the extra 14 seconds I haven’t had time to piece together?

A flat out denial by interim Executive Director that the Library Board has statutory authority to review the Library’s Budget. I did another screen recording in case the video is again removed and or doctored.

Garrity: “The statute requires I do it.”

Pegram: “It does not. John. It does not.”

John: “Do you want me to read it to you?”

Pegram: “Sure. Go ahead.”

Watch the clip and listen to the tone. You decide if the tone is one an employee should use with an employer. Or if an employee should fight so hard to hide documents that an employer has a right to see.

Here is a link directly to the time stamp where it occurs.

The edited content reveals why library staff worked after hours to conceal their sunshine law violation. The removed segment captured interim Executive Director Pegram directly contradicting board members about their statutory authority to review the library's budget.

When board members asserted their legal right to budget oversight, Pegram responded with a flat denial: 'It does not. John. It does not.' When offered to have the statute read aloud, she replied, 'Sure. Go ahead'—the tone suggesting an employee challenging her employers rather than providing requested information.

This exchange explains the systematic transparency obstruction documented throughout this investigation. If the interim director believes the elected board lacks authority to review budgets, her resistance to public records requests and video editing to hide confrontations follows logically.

The Simple Request That Exposed the System

On March 29, 2025, I submitted a straightforward public records request to the Christian County Library, seeking basic budget information that taxpayers have a right to see. What followed was a masterclass in bureaucratic obstruction, revealing how public institutions can weaponize administrative processes to avoid accountability.

The library's response? A staggering $185 fee estimate, justified by claims that the records were stored in "specialized and highly technical management software that entry-level employees are not trained or authorized to access."

The reality is that the library uses QuickBooks.

When QuickBooks Becomes "Specialized Software"

In her detailed April 4 response, Interim Director Tory Pegram explained why taxpayers would need to pay $185 to see how their tax dollars are spent:

"Many of the records you are requesting here are not just sitting in paper or digital files somewhere but will need to be pulled from bank and financial management tools that only administrative staff are trained and authorized to be able to access and use."

"Administrator time will also be required to pull records from bank account and other financial specialized and highly technical management software that entry level employees are not trained or authorized to access or use."

This language portrays a complex, enterprise-level financial system that requires specialized expertise to navigate. The truth is more mundane: the library uses QuickBooks, the same accounting software used by millions of small businesses nationwide—software specifically designed for non-accountants to use easily.

Standard budget reports in QuickBooks can be generated with a few mouse clicks. Any administrative assistant familiar with basic computer operations could produce these records in minutes, not the 11+ hours the library claimed would be necessary.

On May 27th, I finally was able to raise the funds to pay for the extortion like fees to get the budget information. I sent an email. This was two days before this video came out.

After demanding $185 for budget documents, the library has failed to respond to this reporter's agreement to pay their fee. The May 27th email authorizing payment has gone unanswered, violating sunshine law requirements for timely responses to records requests.

The timing raises questions: two days after the payment authorization, staff uploaded an edited video removing interim director Pegram's denial of board budget authority. Missouri sunshine law requires government entities to respond to records requests within three business days.

The Supreme Court's Warning About Fee Obstruction

The library's fee structure directly contradicts recent Missouri Supreme Court precedent. In Gross v. Parson (2021), the state's highest court specifically condemned the practice of using excessive fees to discourage public records requests.

The Court held that charging excessive fees "puts the transparency intended by the Sunshine Law out of reach for the average citizen and in some cases even deters requesters." The justices recognized that public bodies cannot be allowed to "test the determination of anyone requesting its records" by imposing prohibitive costs.

In an earlier case, State ex rel. Missouri Local Government Retirement System v. Bill (1996), Missouri courts established that "forcing a plaintiff to bear the governmental body's expenses would effectively deny public access to documents" and that agencies cannot "test the determination of anyone requesting its records" by imposing excessive costs.

The Christian County Library's approach fits precisely the pattern these courts rejected: claiming administrative complexity where none exists, inflating time estimates, and pricing transparency out of reach for ordinary citizens.

A Pattern of Avoiding Oversight

The fee obstruction appears to be part of a broader pattern of transparency avoidance at the library. Despite my explicit request that all communications be shared with the Board of Trustees and the library's attorney, standard practice for ensuring proper oversight, Pegram explained why she wouldn't comply:

"There is nothing in state law that requires the board or contracted legal counsel of a government agency to be cc'd on sunshine requests or responses. In fact there are risks involved with openly cc'ing all five individual board members on any written correspondence..."

This response reveals a troubling attitude: rather than embracing transparency and board oversight, the interim director actively seeks to minimize it, finding excuses to keep the governing body in the dark about public records requests.

The Legal Framework They're Violating

Missouri law creates clear obligations that the library appears to be systematically ignoring:

Treasurer's Statutory Rights

Missouri library statutes (RSMo 182.060, 182.640, 182.707) explicitly require library boards to elect treasurers and grant them specific responsibilities for financial oversight. RSMo 181.060 requires "the librarian of the library together with the treasurer of the library" to certify annual tax income and financial information to state authorities.

The statutes mandate that budget approval requires "the affirmative vote of a majority of the full board of trustees." A treasurer cannot fulfill their statutory duty without access to financial information.

Public's Right to Information

Missouri's Sunshine Law (RSMo 610.010 et seq.) "applies to all records, regardless of what form they are kept in" and creates a presumption that meetings and records should be open to the public. Budget documents are specifically designated as public records under RSMo 67.060 and are available for public inspection during reasonable hours.

Missouri law requires that "no expenditure of public moneys shall be made unless it is authorized" and that budget documents "must be kept on file" as public records. The treasurer's oversight role is essential to ensuring legal compliance.

Video Recording Integrity

Missouri law specifically provides for "the recording by audiotape, videotape, or other electronic means of any open meeting." Once they choose to record, they create a public record.

The Sunshine Law applies to records "regardless of what form they are kept in," and public bodies "cannot avoid a records request by destroying records after it receives a request for those records." This principle extends to the alteration of records.

More seriously, RSMo 575.100 criminalizes altering, destroying, suppressing, or concealing "any record, document or thing with the purpose to impair its verity, legibility or availability in any official proceeding or investigation." Video recordings of public meetings are official records.

The Criminal Implications

The evidence raises questions about potential violations of multiple Missouri criminal statutes:

Tampering with Physical Evidence (RSMo 575.100): Altering public meeting recordings to remove discussions of statutory requirements

Filing False Documents (RSMo 570.095): Misrepresenting software complexity and administrative requirements to justify excessive fees

Official Misconduct (RSMo 575.320): Public servants engaging in misconduct in their official capacity

The pattern is clear: when faced with legitimate oversight requests, the library both prices out access through deceptive fee justifications and actively edits public records to hide contradictory evidence.

The Cost of Accountability

When public institutions can charge $185 for basic budget information while simultaneously editing meeting videos to hide legal discussions, democracy suffers. The Christian County Library's approach effectively creates a system where transparency is available only to those who can afford it—and even then, only in the edited version the library chooses to provide.

Consider the arithmetic: For many Missouri families, $185 represents a significant expense—money that could be allocated toward groceries, utilities, or other necessities. By pricing public information out of reach while doctoring the "free" video records, the library ensures that complete accountability remains largely inaccessible.

Missouri Courts Have Seen This Before

The library's tactics aren't new. Missouri's Sunshine Law exemptions "are supposed to be construed as narrowly as possible to further the openness of government." Courts can award penalties up to $1,000 for unknowing violations and $5,000 for purposeful violations, plus attorney's fees to prevailing parties.

The Missouri Supreme Court has made clear that government bodies cannot use administrative barriers to obstruct legitimate public oversight. The combination of fee obstruction and video editing suggests a level of intentionality that could trigger the higher penalty structure for purposeful violations.

Questions That Demand Answers

The Christian County Library's approach raises serious questions:

Why does a public institution claim that QuickBooks constitutes "specialized and highly technical management software"?

How can 11+ hours of work be justified for generating standard financial reports?

Why are public meeting videos being edited to remove discussions of statutory requirements?

What statutory obligations was Pegram discussing in the 2+ seconds cut from the public video?

Who authorized the editing of public meeting recordings?

What other information might be hidden behind prohibitive fees or selective editing?

The Simple Test

Here's how citizens can test their library's commitment to transparency: Ask who uploads public meeting videos to YouTube. This simple question requires no "specialized software," no extensive research, and no administrative review.

If they can't answer that basic question promptly and without fees, you've learned everything you need to know about their attitude toward public accountability.

The bottom line: The library cannot simultaneously claim to operate under Missouri law while denying access to information that Missouri law requires them to maintain and provide—and they indeed can't edit public records to hide discussions that contradict their public statements.

I care enough about the Library and the Library Board to bring this transparency issues to light. My silence on this issue will not serve the community. No one pats me on the back for investigative journalism.

The Christian County Library was contacted for comment, but did not respond by publication time.

David Rice is the editor of HickChristian News and has been investigating government transparency issues in Southwest Missouri since December 2023.

Share this post